You’ll recall the scene in the movie Apollo 13; astronauts need an improvised air purification system and a bunch of engineers NASA keep in the basement are told to "make this fit that in six hours, using only what's on the table.” What’s on the table is what’s in the capsule. It’s a dramatic scene and one that made me, a manager at the time, think about 3Vs. Not the 3Vs of Ideas for once but the corporate culture Vs.

Mind your fraktaline business

In The Fractal Organization I said that we should try to make our organizations like fractals – consistent no matter where you look or at what scale. It was sunny when I wrote that and I was feeling optimistic. It’s cloudy as I write this and grudgingly acknowledge that all organizations are, or eventually become, fractals. The only question is whether it’s by design (which is good) or by accident (which can be good but more often is bad). A pattern will inevitably form – be it a snowflake, a succulent plant, or a SNAFU. Regardless, we call it corporate culture.

A corporate culture may be founded on a big idea but it is built by the accumulation of tiny things, like a sand bar. And it shifts like a sandbar too.

Glue-ons

So far as we know, every solid thing in our Universe is made of the tiniest of things, quarks and gluons. They are the Lego blocks of protons and neutrons, the Lego blocks of atomic nuclei. That’s how small they are. All things, no matter how big and complex, are made of small things.

Organizations are not made of quarks and gluons because they are not things. They are ideas. Many are legal fictions and have legal rights (Although in most places, not civil rights). Yet all their remarkable complexities are repetitions, elaborations, and combinations of a few foundational ideas.

If we get those ideas right, and stick to them – occasional slip ups are forgiven – our organization will be alright.

But back to our Apollo support team. What was source of their magic spark? On one level, duct tape. The scene actually happened more of less as portrayed in the movie but the real team leader later said that as soon as he saw they had duct tape on the table he knew it would be easy. More importantly, they also had something else, even more universally useful than duct tape, clarity of vision, values, and vital information.

Why is culture so important?

Dear reader, this section glosses ground I’ve covered so it’s a bit like a choose your own adventure book. If you already think corporate culture is vital, you can either ignore all the links or, better still, jump to the next section.

Corporate culture hardly mattered in the Industrial Era of long run production. Replication entails adherence to standards. Standards are measurable and enforceable. And, to the extent it mattered, workplace culture was shaped by place and local authorities and therefor shared.

Sadly those golden days of sullen conformity couldn’t last.

One plausible estimate is that our collective knowledge doubles every 10 to 15 years. Since our brains aren’t doubling our ignorance must be. Add to this that information is no longer distributed vertically mostly locally, but is instead widely and unevenly distributed horizontally, and it is impossible for one person or even one organization to know what is possible. So, we depend on the knowledge of others.

A centralized organization acts only according to the knowledge of its managers. That’s too small a base. Long run production has been replaced as the competitive edge by relationships, specialists, and idiosyncratic contexts.

That entails teams and teams depend on social legitimacy. (See the second part of Elon, Run Your Business Like A Government! and The Fractal Organization.)

But decentralizing has its own problems.

The horizontal vector of information that makes us more dependent on teams makes it harder to hold them together. For one thing, vertical information from managers say, faces a lot more competition from horizontal information from everyone everywhere. For another, we have personal information filters - news nozzles. The upshot is that organizations can no longer rely on place and authority to create a shared culture.

On top of it all, more stuff available in the market and smart tools make individual autonomy cheaper. (On The Shoulders of Ye People)

Above all, we want our people to make the most of opportunities and resources with minimal but incisive direction, like the Apollo engineers. Cue culture.

How does a decentralized organization remain coherent?

People act in accordance with their perceived context. But, as you saw, if you read the section, context is more idiosyncratic now. Corporate culture is the best chance of having a shared local context.

One of the greatest difficulties in curating a corporate culture is that it is usually articulated in high flown, abstract terms. This makes it hard to grasp. It’s easier to grapple with if we divide it into three basic elements: vision, values, and vital information.

Vision: what the organization aspires to do.

Values: the principles determining how it does things.

Vital information about the organization1: what it really considers most important, a grab bag of customs, practices, feedback, resource allocation, and what it chooses to measure, reward, frown on, and punish.

Of the three, the most powerful is vital information. It determines the effectiveness of the first two. Management has less control over this than most managers realize because it is more often gleaned from individual experience than declared by management.

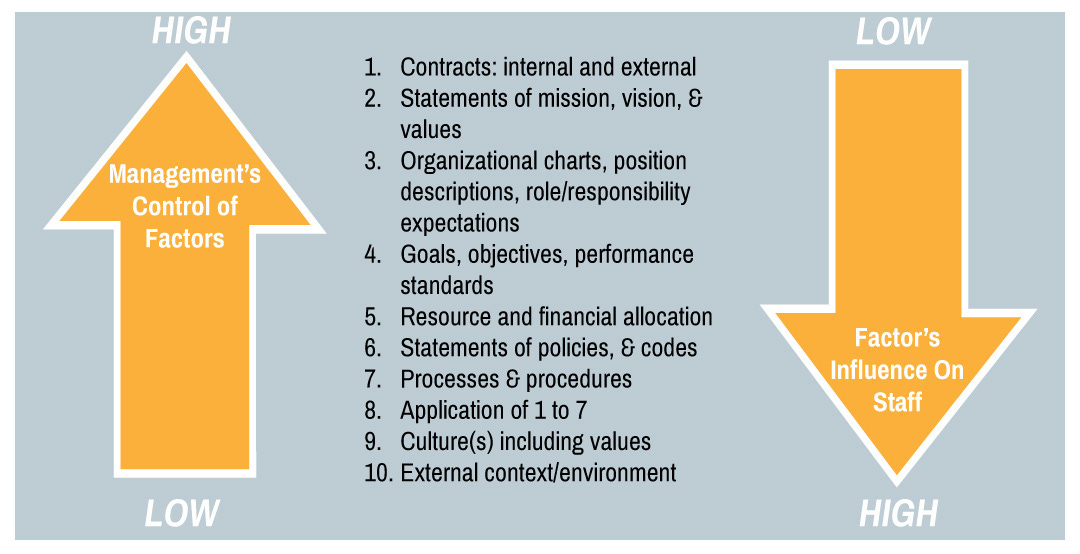

Here’s the chart from Management’s Job Has Never Been Harder and Its Tools Never Softer

Management may promulgate the best procedures manual in the world but if the vital information is that no one pays attention to it, no one will. If the vital information is that punctuality is more important than productivity people will enjoy a leisurely breakfast in their cubicles.

Vital information is where we find the real vision and values of the organization.

Laws, codes, policies, norms, processes, contracts, behaviours are deliberate attempts to embody vision and values in vital information. How they are observed and enforced will determine whether the organization’s fractal is a pattern of principle or expedience.

Alignment of the 3 Vs of organizations is crucial. In a properly functioning organization the vision and values are the touchstone for all vital information. The first two Vs only get a bad name when they conflict with the third. And people, staff, suppliers, customers, regulators, are always watching and sensing which information is vital. So “vital information” must be actively curated and that’s tough at times.

The price is the prize

Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean fleet in the darkest years of World War Two was criticized by an officer of another navy for the number of ships he lost supporting the evacuation of Crete by the British Army in May 1941. “It takes three years to build a destroyer,” the officer said, and Cunningham replied, “yes, but it takes 300 years to build a tradition.”

Keeping vision, values, and vital information aligned extracts a price but it produces evidence. The proof of a vision or value is what you are prepared to sacrifice to maintain it.

It is impossible to be invariably consistent. And it is hard for a senior manager to concede discretion to discussion, and position to principle but it is an opportunity to create the vital information that the organization lives by its vision and values.

Looking back on my management career I can only hope people accepted my inconsistencies as momentary lapses and not course changes. One thing I will claim though is that I always knew that the true sign of a successful culture wasn’t when I referred to our vision and values but when I deferred to them – when staff used them to challenge me.

Now what?

If vital information is the most powerful of the three, values is the most misunderstood. That’s next.

As you’ll see in the comments, I wasn’t as clear as I ought to have been that “vital information” does not refer to, say, events external to the organization. They may constitute information and may be in many respects vital to it. But not about it. For instance, If you work for a relief agency it is vital you have information about a flood in your area. But, “vital information”, as I use the term in this post, would be that everyone in your agency will turn to; that your managers know their jobs and will work just as hard as the hardest worker, and you will get resources to the people in desperate need. Or, not - and the whole operation will be a shambles, and it’s the last time you answer the call with that bunch.

Doug, before we leave Apollo (different mission)I think it is important to remember JFK’s speech. In it he said "First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

In my opinion that is one of the best vision statements ever. It is clear and sets a deadline. In corporate parlance, it is a BHAG. A big, hairy, audacious goal.

He goes on to say “and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.” He says it will be hard and gives permission to throw everything at it. Fantastic! Inspired leadership. Aaahhh. The good old days. BTW, thank you for your posts. Be well. R

Doug, a key factor the Apollo team also had was a very clear sense of urgency which was reinforced by the also shared outcome of failure. Nothing focuses the mind more than the prospect of your own hanging the next morning.

Do the values and vision help an organization proceed forward until new, confirmed and accepted vital information replaces the old? Often organizations have to make decisions (or don’t make them) because information is not known, incomplete, etc. Things still happen. Is it that inertia is vision and values? The culture of the organization is still in force and depending on both the culture and the circumstances it will save the organization or drive it into a worse position.

Surely, the fine and brave people of the Ukraine are not awaiting vital information.