Pyramid scheming

In 1676 Isaac Newton wrote “If I have seen further than others, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of ye giants”. The popular belief that Newton was the first to discover the benefits of standing on giants is not correct. The quote can be traced to the 12th century and presumably the practice predates that. The belief that Middle English speakers said “yee” for “the” is also incorrect. The Y in “ye” is a simplified version of their letter thorn which represented the “th” sound. In other words middle English speakers pronounced “ye giants”, more or less, “the giants”. Ditto tea shops and pubs.

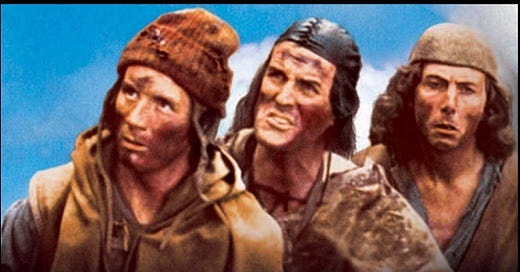

Fascinating as ye stuff is, the key point is that, in the Ideas Era, a pile of ordinary people works just as well as a giant if they are stacked correctly.

Stacking them is management’s responsibility. The problem is, stacking them has never been more difficult. In the next post I’ll explain why. But now for something completely contemporary.

We all recall the scene in Monty Python’s The Search for the Holy Grail where an onlooker recognizes the king “because ‘e’s the only one not all covered in s….”. The time when high authorities had exclusive access to sanitation is gone, as is their monopoly on education, information, and expertise.

The traditional information pyramid was a key source of management power. Now managers are no more likely to have valuable information than anyone else. All but the very poorest people have easier access to more information than did the ultra-rich only thirty years ago. When an information pyramid exists, it is likely to be an inverted image of the organization chart. If anyone occupies the commanding information heights, it is specialists. The same goes for ideas. Even in metal bashing factories, line workers have useful ideas to contribute to management’s deliberations. In the more creative services, the workers are the business.

The central fact is that, in the Ideas Era, it is impossible for one person to know what is possible. Everyone is in the same boat as Matt Ridley and his fishing rod. When nearly everything is something “that no one knows how to make”, managers are dependent on the knowledge of their staff and suppliers.

Pyramid teaming

Managers and their gurus responded instinctively, and new truisms appeared. “Command and Control (C&C) is dead.” “Break down the silos, networks and teams are the answer!” “The key is to innovate!” “Leaders are everywhere, managers are plodders. Don’t be a plodder! Get charisma and think outside the box!” “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” so instead of a firm hand on the tiller, be a “coach”, “servant leader”, “thought leader”, “innovation leader” and, best of all, “the leader everyone loves to follow”.

Whole books have espoused one or other of these truisms as groundbreaking, spontaneous and unique insights. Taken separately, each is like the Mississippi, broad, muddy, and shallow. Strung together like this, they are the cliches they have become.

I’m not saying they’re wrong. Just that that it’s wrong to present them as newly revealed, universally applicable truths.

It is a capital mistake to assume that managers of today see what their predecessors were too dunderheaded to see, as is often implied and sometimes said. To see change in terms of people moving from wrongheaded to right headed deprives us of lessons from the past that could be useful in similar situations.

Saying that everything’s changed is no more helpful than saying nothing’s changed. When considering what’s changed, it is important to consider why and, just as importantly, what hasn’t changed and why not.

A little humility is useful too. As John Maynard Keynes wrote:

Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.

Defunct economists are not the only source of misplaced assumptions and slavery is not a word to throw around lightly but, when we understand how context prompted a bit of advice, we are better able to utilize it appropriately and to anticipate other contexts and responses.

So let’s do that.

Far from being separate phenomena, these truisms are effects with causes in common.

Despite the many obituaries in management books, command and control isn’t dead. It is still required when the org chart side of the corporate coin paradigm is facing up. Without silos we have haystacks, notoriously disorganized and hard places to find things. In situations where accountability is required, silos are best. Before you think outside the box check around inside the box to see if the issue’s been dealt with in the past. Trying to be The Leader all the time isn’t just egotistical; it’s also a big problem and, ahem, a greater selection of problematic behaviours is not the solution - and that goes double for trying to be the leader everyone loves to follow. As I argue in The Org Chart is a Half Truth - the Sequel, leadership is a liquid and a corporate resource and not a management monopoly.

Teaming

The Ideas Era emerged, not because we got smarter, but because new technologies drove the 3Vs of ideas. Our dependence on teams is not because today’s generations are more social than their predecessors. Collective knowledge is expanding, the pace of change is faster, innovation is easier. The speedier and more scattered is information, the more important procuring, cultivating, and integrating expertise is.

I identified three key elements of the Ideas Era which directly affect how we organize, lead, and manage are:

1. More is available in the market, more readily, for less.

2. Collective knowledge is expanding, probably exponentially.

3. Information is widely and unevenly distributed horizontally.

They are the reasons for the truisms – two and three in particular. As we all know less and less of more and more, our reliance on the knowledge of others grows. Henry Ford’s Model T had fewer than one hundred different parts, so it was possible for Ford to know the sum of human knowledge about his cars. His generation of senior managers was the last that knew exactly how to make their products. The modern car has over 30,000 different parts. Few vehicles can be said to be made anywhere. Larger components might be manufactured near the point of final assembly, but small components are sourced globally. Elon Musk cannot know a fraction of the sum of human knowledge of electric cars, let alone rockets - not to mention computers to run them and robots to build them.

“Across all scientific fields, single-author research papers have declined from 30% in 1981 to 11% in 2012. In some fields, scientific papers now average five authors. By 2013, 90% of papers in science and engineering journals were written by teams.”1

When I was a deputy minister, I was constantly reminded that the biggest idiot in the Justice Department knew more about his job than I knew about his job2 – assuming the biggest idiot was male and presuming he and I weren’t me.

I was a senior manager several times and each time I was expert at a few things, a layperson at many things, and ignorant of most things. Success depended on picking the things it was important for me to know, patrolling the boundaries – particularly values – it was important for me to control, and cultivating the expertise around me so it deployed appropriately.

I did this better when I stopped trying to be the leader of managers and instead was the manager of leaders and integrator in chief. That’s why it is vital to completely untangle leadership and management in your own mind.

Why is “integrator” not yet a professional designation?

Teeming

And now the bad news. In addition to the three characteristics of the Ideas Era that make us more dependent on teams there are four more that make it harder to hold them together.

Personalized information filters - news nozzles - are available and unavoidable.

Individual autonomy is cheaper.

Context is individually tailored.

More of value is intangible and intangibles are more valuable – and intangibles are infinite.

We’ll look at them next in Management’s Job Has Never Been Harder and Its Tools Never Softer.

Strategies for Team Science Success, Kara Hall, Amanda Vogel, Robert Croyle, eds. Nature 2019

I’d thought this was my novel insight until I found that Galileo Galilei had said “I have never met a man so ignorant that I couldn’t learn something from him,” rebutting one assumption and casting doubt on the other.